The twinkle lights will soon be strung, and the greenery with red bows will be hung, it’s beginning to look a lot like Christmas, and the lectionary serves us up . . . Apocalypse.

“signs in the sun, the moon, and the stars, and on the earth distress among nations confused by the roaring of the sea and the waves. People will faint from fear and foreboding of what is coming upon the world, for the powers of the heavens will be shaken.”

What’s up with that?

To most twenty-first century residents of the industrialized world, apocalyptic imagery just sounds weird. Whether from Revelation or Daniel or from this little apocalypse in Luke, the words just sound creepy and strange. Their misuse as texts of terror in the hands of charlatans and theological terrorists who want to frighten their followers into submission simply adds to the sense that these passages serve only the delusional among us.

What we find, however, among Christian communities who live under the threat or reality of violence and sudden death is that these apocalyptic passages are not texts of terror but of hope.

For Christian communities historically in South Africa under apartheid or today under ISIS rule in Iraq or Syria, the end of the world in a violent conflagration does not seem to be the stuff of an over-active imagination; rather, it seemed or seems the most likely outcome. The only question is when, and nobody knows the day or time.

That is the kind of situation that produced apocalyptic texts–Jeremiah’s community under attack from the Babylonian empire, and Luke’s community under attack from the Roman emperor. Destruction seemed inevitable. The only question was the day or time.

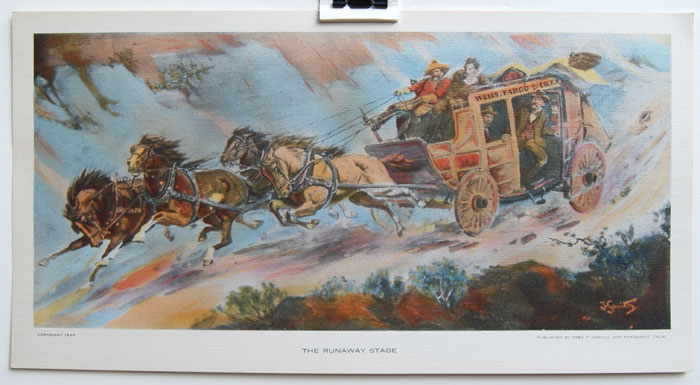

So, in hauling back on the reins of the runaway Christmas stagecoach, the church hopes to slow us down just long enough that we can listen. We don’t have to listen long to the news to hear the voices of our brothers and sisters living in an apocalyptic nightmare.

If we turn off the news and listen, we may even hear the voice of our neighbor, a friend who lives in her own little exile of loneliness; we may hear the voice of someone who lives in his own impending apocalypse of financial ruin or deteriorating health.

We may even hear the voices of doom in our own lives.

So, what then?

Beneath all the noise of the secular Christmas machine, the Bible calls out this word with a still small voice: hope.

The event we are preparing to celebrate is more than the birth of a very special baby to a poor Jewish couple in a stable in Bethlehem. The event we celebrate is incarnation. It is God becoming human flesh.

Here we have scripture written by people who can see the end of the world as they know it from where they stand; and still, they see reason to remain faithful and hopeful.

The extraordinary proclamation of Advent is that no matter how deep the darkness, no matter how cruel our adversaries, we are not alone in this world. We live in a world into which God has come in human flesh in Jesus Christ, and a world into which God enters still.