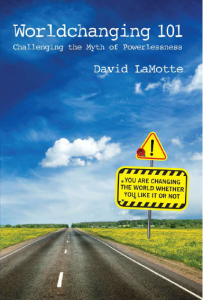

Worldchanging 101: Challenging the Myth of Powerlessness, by David LaMotte

David LaMotte is a dangerous man. His demeanor is gentle. His acoustic guitar and singing voice depend on a microphone to be heard in a crowded room. His speaking voice has a velvet quality that you will hear through his writing whether or not you have ever heard him speak.

That’s what makes him so dangerous.

The myth of powerlessness serves me well. As long as I know I am no extraordinarily courageous hero like Mandela with extraordinary skills of persuasion like Martin Luther King, Jr., with an extraordinary opportunity to take a stand against injustice such as Rosa Parks, then I can come to terms with the idea that changing the world is somebody else’s job. I’ll get out and vote in major elections (but not a mid-term, that would be pointless) but I know I live in a red state so the outcome is predetermined. I might even complain on Facebook about some huge injustice the government or some large corporation inflicts on society. But, let’s face it, as an ordinary citizen with ordinary skills and relatively little wealth to influence the political process, my words and actions are a puff of flatulence in the wind. Nothing I say, write, or do will move the needle one bit on the justice meter. Activism on my part would be tilting at windmills.

In Worldchanging 101, David LaMotte gently, nonviolently, and playfully eviscerates my cynicism with a blade so sharp it hurts not a bit until he has finished and I stand gutted of my comfortable worldview with the pieces chopped into a bloody pile at my feet.

David LaMotte’s argument against the cynicism of our age is that it is unrealistic:

Imagine being in an anti-Apartheid organizing meeting at a U.S. university in the late eighties, when Nelson Mandela was still in jail, the United States government still supported the Apartheid regime, and things looked quite bleak in South Africa.

What if you had stood up and said, “OK, here’s what’s going to happen: Nelson Mandela will be released from prison, and then about four years later, South Africa will have free and fair elections in which he will be elected president. There will not be retributive genocide of Whites, and though there will still be many serious issues to deal with, South Africa will largely recover economically and politically. It will end up adopting one of the most progressive constitutions in the world, enshrining civil rights as few have done. I think that’s what’s going to happen.”

How would people in that meeting have responded? I imagine they would have laughed you out of the room as a lunatic, idiot, or both. You would have been considered a starry-eyed dreamer.

But who in the room would have been most in touch with reality? Who had the best handle on what would happen in the real world?

As a culture, we have come to a place where we equate cynicism with realism and hope with naiveté. But that is, well, unrealistic.

When I argue that I am no Mandela, LaMotte destroys the hero myth—the idea that grand social change comes primarily from the efforts of high-profile heroes who are different from us ordinary peons who must wait on the actions of the charismatic and courageous few. He tells stories of ordinary people who did ordinary things such as attend a meeting, invite a friend to a meeting, give somebody a word of encouragement, volunteer to take minutes, learn to play guitar, attend a training event to learn non-violent communication strategies, or make a pecan pie.

Those little actions gave Rosa Parks, Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., Mandela, and other visible leaders a foundation to tip over mountains of injustice.

If you know David LaMotte, you probably know of his recent arrests related to the Moral Monday demonstrations in the North Carolina statehouse. With self-deprecating humor, he recounts the story of two arrests and his time in an overcrowded jail with his co-conspirators who were charged with disrupting the North Carolina legislators’ attack on civil rights by chanting scripture (Micah 6:8) and “some version of disturbing the peace, which included ‘loud singing’. I’m particularly proud of that charge, though the truth is I’m a rather quiet singer. I never would have made it in the days before microphones.” (p. 179)

LaMotte insists that though those who were arrested were more likely to have their faces on the evening news, the contributions of those who were not arrested play just as important a role in the ultimate success of the movement in convincing the governor to veto the most egregious of the bills and preventing an override. The lawyers who represented them, the people who made and brought sandwiches to the church in the middle of the night after they were released, those who crowded the fellowship hall playing guitars, singing, and laughing and caring for the jailbirds after their ordeal, they, too, are part of changing the world.

I have heard David LaMotte perform his music on several occasions, and I have been privileged to participate in a couple of songwriting and peacemaking workshops with him over the last fifteen years as his thinking about this book developed, so I have a collection of my favorite David LaMotte aphorisms. One of my very favorites does not appear in this book, but it is consistent with its message: “Anything worth doing is worth doing poorly.”

If we wait until we know how to do something extraordinarily well, we will never do it enough to get good at it, whether that is playing guitar, writing songs, or changing the world for the better. The key is to take one step at a time. Do it poorly, do it better, then do it well.

If you want to do something worthwhile with the years of life you have remaining, here is a small step that will make you a more joyful person and make the world a better place because you were here: read this book.

You can order it directly from David in paperback or any major e-book format here. You can find it on Amazon here, though last time I looked, they had sold out.

If you would like to read my reviews and articles as soon as they are written, join my community of readers here.

Sounds like a good book for a Sunday School class!

It would be, Martha. I thought the same thing