I was afraid, and I went and hid your talent in the ground.–Matthew 25:25

From a family systems theory perspective, we can hear two different conversations occurring over the recently released torture report. One conversation is self-differentiating and the other is reactive. The self-differentiating conversation can help us think through our nation’s moral and national security priorities. The reactive conversation dooms us to name-calling, reinforcement of social and political divisions, circular arguments, and a spiral of ever-increasing anxiety that helps nobody except those who sell advertising on fear-mongering news shows. [No link necessary. You know who I mean.]

In both conversations, we hear voices in favor and voices opposed to the interrogation methods used on detainees outlined in the report.

In a reactive conversation, people speak and act out of their automatic reflexes, especially fear.

In a self-differentiating conversation, people speak and act out of a clearly-articulated moral framework.

In the reactive conversation, even when the participants appeal to reason, they construct reasonable-sounding arguments to support their emotional reaction to the report. Whether one responds with revulsion to the reports of forced rectal feeding and freezing to death a man whose affiliation with terrorism was never established, or with anger that the report was released because it fans the flames of our enemies’ hatred, the argument that follows will be constructed from the foundation of that reflexive feeling. Cherry-picking facts always reveals an emotional reaction rather than a thoughtful self-differentiated argument. Evidence that supports that feeling will be included and evidence that supports the opposite will be dismissed or ignored.

The self-differentiated argument begins with identifying a moral framework and ethical foundation and builds a position and a proposal for action on the basis of that foundation.

For example, arguing in favor of the use of any means necessary to extract information from detainees, a self-differentiated argument begins with John Stuart Mill’s utilitarian moral framework. It builds its argument on the postulate that the ultimate goal of government is the protection of its citizens. Since that goal stands supreme over all else, the argument over the use of torture emerges as an argument over whether or not torture is effective in extracting actionable intelligence from detainees that will give the CIA the ability to catch enemies or prevent plots against the U.S. from succeeding. Killing or torturing some innocent people is the necessary price of attaining a greater value.

Within this same utilitarian moral framework, the argument against the use of torture argues that the cost is greater than the benefit—that the use of torture yields very little if any actionable intelligence and that it yields a great amount of misinformation from detainees that just want the torture to stop so they say whatever they believe their interrogators want to hear. Further, the utilitarian argument against torture claims that the use of torture fans the flames of hatred against us and puts our own citizens who are prisoners of war at a higher risk of being subjected to similar treatment at the hands of our enemies.

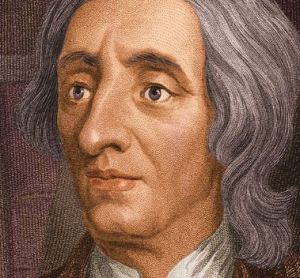

The argument that I made in a previous post stands on a different moral foundation, a moral framework elucidated by Thomas Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights, based on traditional Jewish and Christian religious values and shaped by the humanists of the Enlightenment, both Christian and secular, especially John Locke. On this moral foundation, I argue (along with John McCain) that the ultimate goal of our government and its agents is to act out of the moral foundation of our country: that all people are created equal, endowed with certain unalienable rights, and entitled to due process in the quest for justice.

In the self-differentiating approach to argument, the position we ultimately take requires two steps: first, articulating the ultimate value on which we stand, the utilitarian commitment of government to protect its citizens at all costs, the commitment of government to act out of its foundational values of human rights, or something else.

Second, the self-differentiating realm of argument weighs the evidence of whether torture serves each framework—whether it makes us safer, if one stands on the utilitarian argument, or whether the interrogation techniques used by the CIA violate our nation’s moral foundation, if we stand on the human rights argument as the ultimate value.

Here are the questions I invite you to consider:

- Are we too far gone toward reactivity and societal regression as a nation to have a self-differentiating conversation?

- Is the idealism of the American revolution (equal rights for all people) obsolete in a day when terrorism rather than tyranny threatens us more?

- From what ethical foundation other than utilitarianism and universal human rights might we find common ground in our national conversation on torture?

- How do you know when a conversation has become more reactive than self-differentiating?

If you would like your free copy of “Cheaper Than A Seminary Education,” a 45-page e-book on reading difficult passages of Scripture in context, sign up for my weekly newsletter here. If you decide it’s not for you, you may unsubscribe at any time.